A few months ago I took another leap of faith into the world of natural deodorants. I say ‘another’ because I’ve tried this leap a few times before but always backpedalled to my ‘normal’ deodorant before long.

I’ve tried the deodorant crystal that you wet before applying. While it was cute and made me feel very earthy, I found it too fiddly to incorporate into my daily routine. Plus, I never had complete faith in its ability and subsequently never tested it with a game of volleyball.

Then I tried the natural deodorant in a pot. This one was a bit more effective than the crystal and smelled great, but due to its packaging the application process was a little more fiddly than the standard roll and go approach. I tried it for a few weeks and but quickly grew tired of the extra step in my routine.

I also tried a mainstream brand that launched an aluminum free version of their normal product. That got tossed within a few days because it wasn’t even effective enough to only wear around the house.

When Wild deodorant adverts popped up in my social media feed I decided to give them a go because they seemed to tick all the boxes:

- the product was natural

- the product was in similar packaging to mainstream brands so no change to the routine was needed

- the case was designed be sustainable in that you simply need to refill it when the deodorant runs out. Instead of disposing of a bunch of empty deodorant cases over the course of a year, you now only need to dispose of the recycled cardboard at the base of your deodorant

Sold.

In addition to the above attributes, I actually find Wild deodorant effective and have been using it for months. But I still have my old product in the cupboard juuuuust in case. And this is where I discovered the parallels between natural deodorant and an electric vehicle.

Both products are effectively better for the environment – particularly if they are adopted at scale and with both, prospect theory is at play.

What is prospect theory?

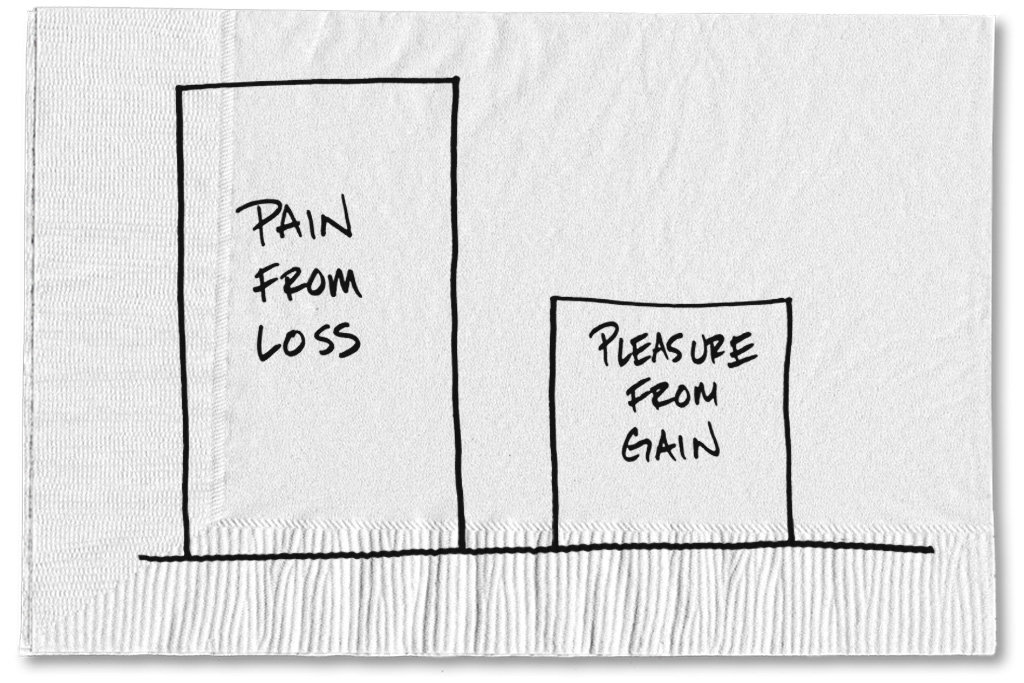

Prospect theory, also known as loss aversion theory, is a behavioural model that shows how people decide between alternatives that involve risk and uncertainty1. According to prospect theory, people tend to be loss averse. Even in a scenario where the risk involved in experiencing potential loss is equivalent to that of achieving potential gain, people are more willing to take the risk involved in avoiding a loss.

In the example of deodorant, the potential loss associated with fully switching to a natural brand (social exclusion) is more important than the potential gains of the use of healthier products on my skin, less money spent in the long run and lower environmental impact.

From the perspective of EV ownership, the potential loss is more commonly referred to as range anxiety – or the fear that your EV will run out of charge before you are able to reach a charging station. But unlike a deodorant scenario which would leave one being unpleasant to be around, the implications of running out of battery are a bit more daunting.

Probably more to the point, the immediate potential losses associated with being stranded (cost, inconvenience, and potential danger) for many are not equivalent to the potential gains of the lower running costs of EV ownership, the exemption from some taxes and a contribution to cleaner air for the wider society.

The point of this reflection is to highlight that it took me three attempts with a natural deodorant before switching to a natural solution that was closest to my current product in terms of packaging, user experience and functionality and I still have a back up, so I believe there are still a few iterations of EV that need to be developed before we see a marked increase in EV adoption.

Hopefully this has challenged you to review whether you make your decision through the lens of loss or gain. Ultimately, if you really want to do something, you’ll find a way. If you don’t, you’ll find an excuse.

Reference

1 – Prospect Theory, https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/prospect-theory/Image sources

Deodorant: Freepik

Prospect Theory: NYTimes